What is VTEC?

How Honda Created a Legend With a 10mm Pin

What does it take for one specific bit of simple, yet brilliant technology to achieve meme status? In the case of Variable Valve Timing and Lift Electronic Control (better known as VTEC), it started out as a way for Honda to offer better performance while still meeting emissions standards and displacement limits at the start of the 90s and arguably gave the company’s automotive division the same kind of high tech street cred their motorcycles already enjoyed.

Tires: Milestar MS932 Sport – 245/45R17

The original VTEC led the way for a whole new slate of variable valve actuation systems from practically every major manufacturer, with a wide range of complexity and effectiveness seen today. Back in the day, it would be hard for anyone to imagine that a simple pin moved by a hydraulic actuator could become such a legend, but in retrospect it seems like one of those “why didn’t I think of that?” inventions.

Best of Both Worlds

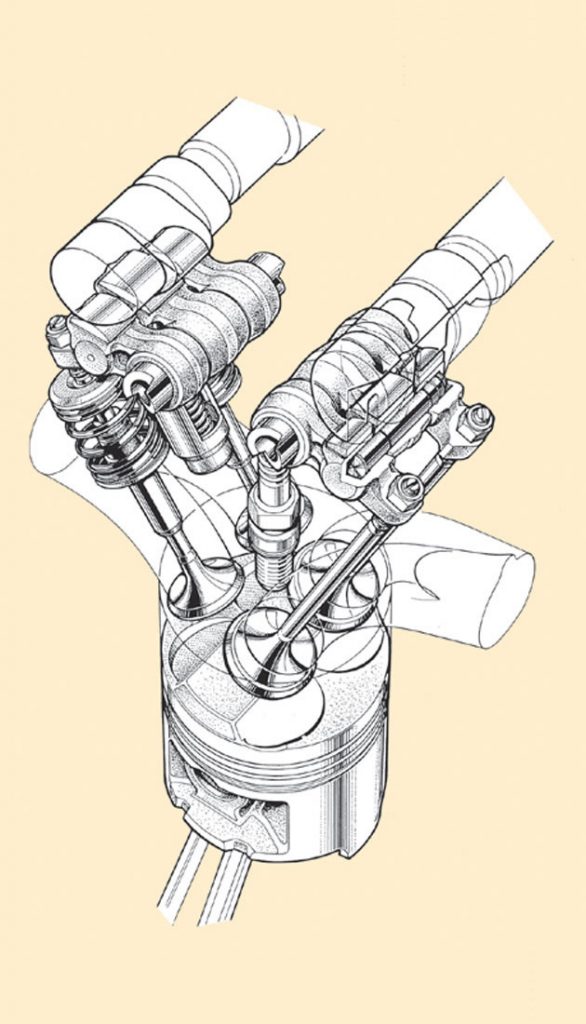

To understand the impact of VTEC on the automotive world, it’s worthwhile knowing exactly what it is and what it isn’t. Conventional piston engines rely on one or more camshafts, turning at one-half engine speed, to control the motion of the intake and exhaust valves. No other single aspect of engine design has a bigger effect on performance, economy, or emissions than the timing and intensity (for lack of a better word) of valve events, and for engines without some sort of variable valve control, every compromise gets carved in steel at the factory and can’t be changed without getting into the ‘wet’ part of the engine.

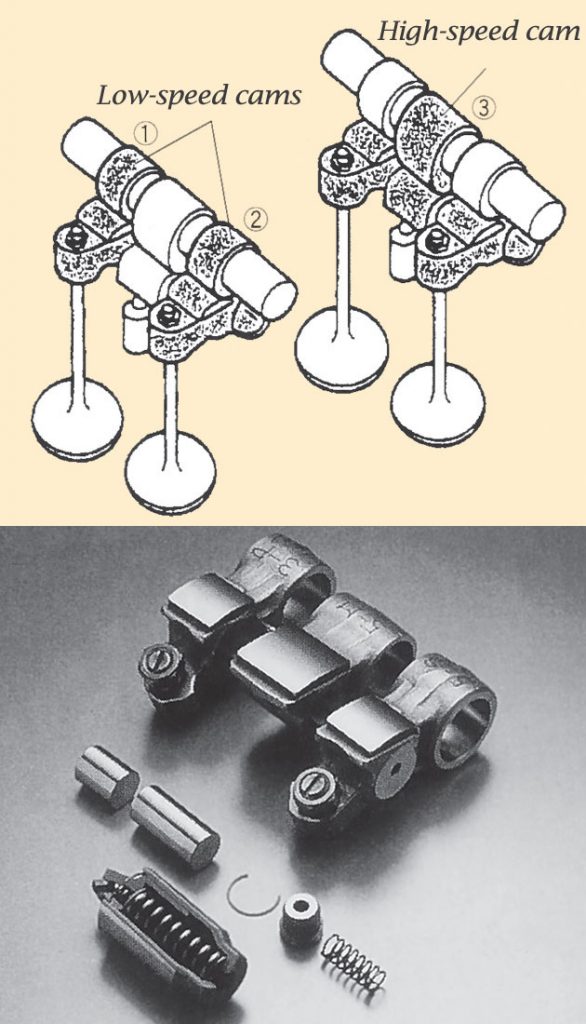

This is important because the physics involved in getting air and fuel into the cylinder and exhaust out mean that a cam lobe design optimized for low-end grunt is going to be unhappy at high RPM and vice versa. At lower speeds, cylinder-filling is improved by having relatively small valves with low lift, trading away some pumping losses in exchange for keeping velocity up in the intake tract, but towards the upper end of the RPM scale, bigger is better and low lift will kill airflow. Similar tradeoffs for valve duration (the part of the 720 degree four-stroke cycle when the valve is open to a meaningful extent) and valve overlap (degrees of crank rotation during which the exhaust valve is still closing while the intake valve starts to open at the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next) also have a big effect on how the engine delivers power.

With a traditional camshaft, it’s one and done since whatever specifications were ground into the lobes at the factory are all you have to work with short of a swap. Hot rodders came up with some work-arounds, of course – part of the skill set of the traditional pushrod V8 racer was ‘degreeing the cam’ which involves using an adjustable timing gear set to move the cam’s timing earlier or later in the cycle, and dual overhead cam engines can use the same strategy plus change the intake and exhaust timing relative to one another to get some adjustability for overlap, but this was strictly something done in the shop rather than on the fly while the engine was running. More crucially, it didn’t change the cam lobes’ profile or lift.

A Stroke of Genius

The solution seems obvious now, but at the time it required asking what sounds like a dumb question – “If the engine runs best with one cam design at low speed, and another at high speed, why not give it two cams?” At its core, that is all VTEC is – a way to put two completely different camshaft grinds into the same engine, and switch between them on demand. That’s much easier said than done, though, especially when whatever you come up with has to be simple enough to produce economically, durable enough to last for a hundred thousand miles or more, and designed to fail ‘gracefully’ and not leave you stranded if something goes wrong.

… that is all VTEC is – a way to put two completely different camshaft grinds into the same engine, and switch between them on demand…

In 1984, Honda launched the New Concept Engine program with goals that included increasing torque and horsepower for their car engines across the RPM range, with an eventual benchmark of achieving 100 horsepower per liter of engine displacement for production engines. Initially, the NCE initiative led to powerplants like the DOHC ZC (forerunner of the D-series engine) as early as 1985, but the real breakthrough came when previous research begun in 1983 into a system intended to improve fuel economy was rolled into the new project.

One of the main players in the NCE project was Ikuo Kajitani from Honda’s First Design Department in their Tochigi R&D Center. “Characteristically,” Kajitani said, “four-valve engines are known as high-revving, high-output machines. And for that reason we knew it would be quite difficult to achieve low-end performance if the engine’s displacement were too small.” He was certain that a solution to the problem could be found in the work done on the fuel economy project in the form of an engine that could change valve timing and lift dynamically during operation.

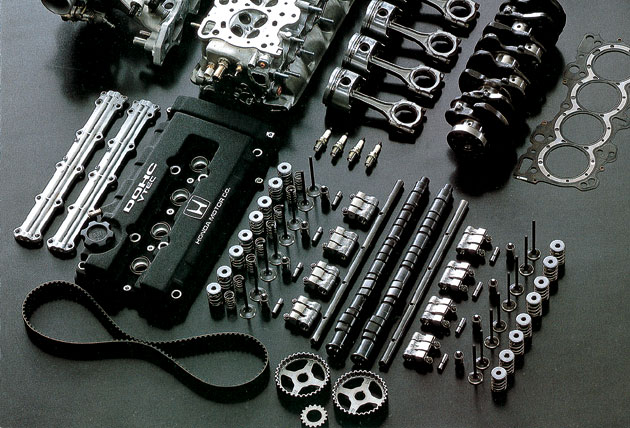

This capability took shape as a very simple but elegant system that uses only a few additional parts compared to a conventional valvetrain. At the beginning, the team had considered around thirty different methods of achieving this goal, but to narrow down the field, priority was given to systems that relied on proven technology rather than novel approaches that might have unforeseen show-stopping flaws. With a mixture of caution and optimism, ideas that seemed promising but had a high risk of being developmental dead-ends were set aside. One of the most important goals was to have a mechanism that could handle 400,000 cycles without failing. In the end, the team settled on the system we now know as the original VTEC.

For each cylinder, instead of a single cam lobe to control valve events, there would be three: Two low-speed lobes with a single high-speed lobe between them. With the system deactivated, each valve would be controlled by its own low-speed lobe, while a third cam follower with no direct connection to the valves followed the profile of the single high-speed lobe. On computer command, a hydraulic valve would send oil pressure to move a pin into place to connect the outer followers to the inner one and lock the whole assembly together, causing the valves to follow the more aggressive center cam lobe profile.

No Magic Involved

Though the concept was simple, there were still significant technological hurdles to overcome. One major example of this was the fact that they needed to squeeze three lobes into the space originally occupied by one, and those lobes would also be operating the valvetrain under higher loads and engine speeds than they’d previously been engineered for. Solving this issue required improvements in both metallurgy and design, but the team achieved their goal (and then some) in time to confidently introduce the new technology for the 1989 model year.

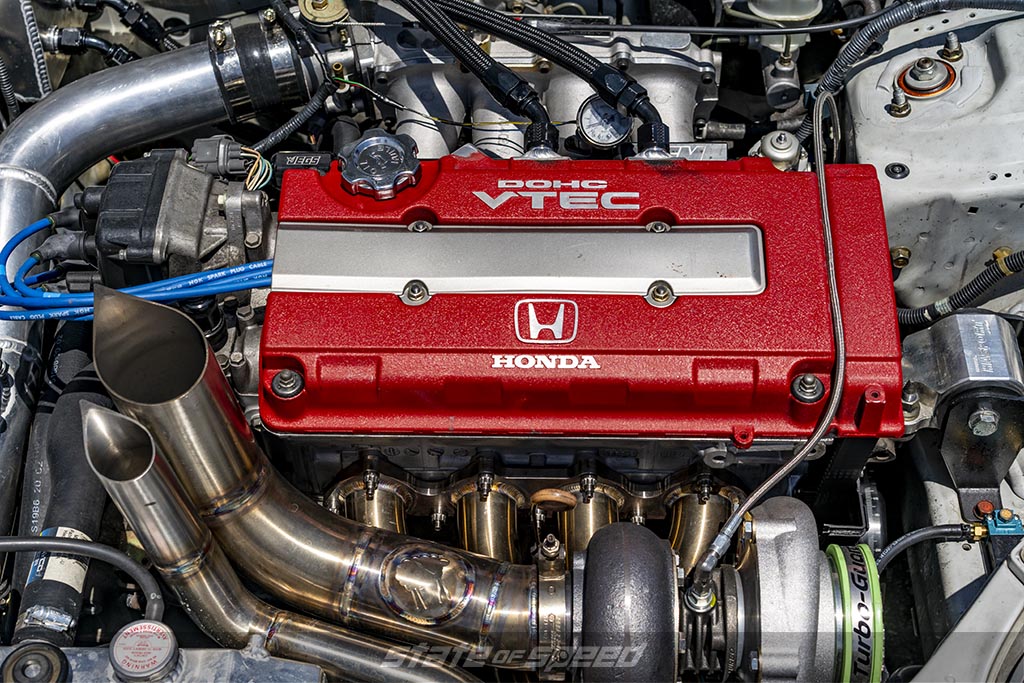

While VTEC in its original incarnation does allow an engine to operate in ways that a fixed valvetrain simply can’t, there’s a widely-held misconception that it’s some kind of super-science that works like hitting the switch on a nitrous system. In reality, what it did was allow Honda to build engines with the ability to change between a cam designed for efficient, clean, and fuel-sipping performance to one with the grind the engineers wanted to use in the first place. As a matter of fact, it’s not uncommon in race applications to use a single-grind camshaft that actually defeats VTEC in order to increase tolerance for abuse and reduce complexity and weight. When street driving isn’t high on your priority list, the flexibility and broad powerband that VTEC allows isn’t as important, but it makes a huge difference in your daily driver.

…it’s not uncommon in race applications to use a single-grind camshaft that actually defeats VTEC in order to increase tolerance for abuse and reduce complexity and weight…

The Bigger Picture

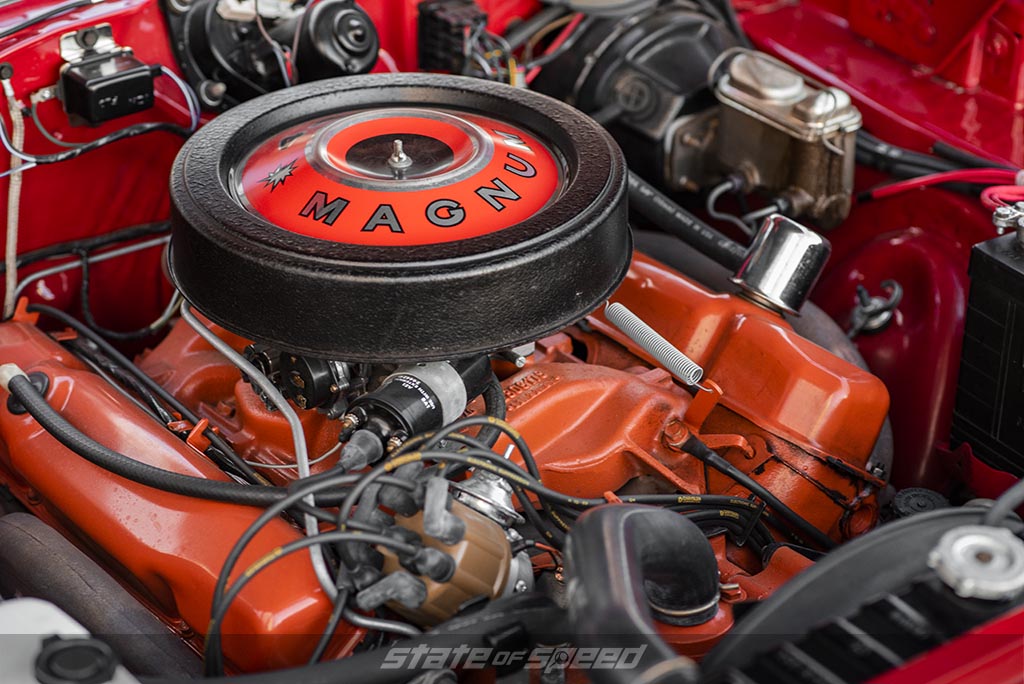

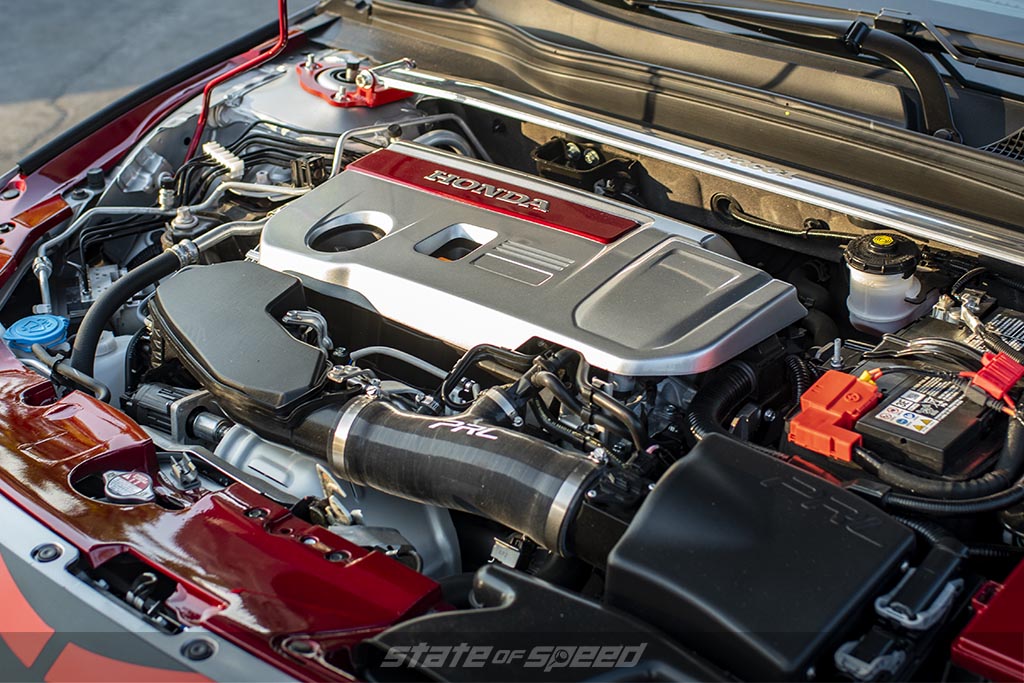

For all the popularity of “VTEC just kicked in” memes, the system actually does what it was intended to do – Allow small-displacement engines capable of high fuel economy and low emissions during test cycles and normal driving to also provide exceptional horsepower when run hard. In the process, Honda managed to turn cars like the Civic from quirky but reliable transportation devices into ones that were actually fun to drive fast. Whether it was their intention or not, you can argue that the evergreen popularity of all the generations of Civic that followed were a direct result of the NCE project and the development of VTEC.

Tires: Milestar MS932 XP+ – 265/35ZR18

Today, every manufacturer has implemented some sort of variable valve timing setup, even for old-school pushrod V8 engine designs. There’s a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms used to describe all the different proprietary ways manufacturers have come up with to adjust valve timing, intake versus exhaust cam phasing, and so on, and Honda has gone on to improve their own engines with VTEC-E, 3-Stage VTEC, i-VTEC, and i-VTEC with Variable Cylinder Management. But the real special sauce – changing to a completely different cam profile on demand – remains at the core of VTEC technology. Until we reach a point where camless valve actuation via pneumatic or electronic direct control finally makes its way from the cost-is-no-concern pressure cooker of Formula One racing to the street, Honda’s approach will likely remain as the best way to change lift and duration on the fly.