Future Classic:

The Nissan 240SX Story

If you sat down with a pen and paper in hand and made a list of all the qualities that define a “fun to drive” car, you’d probably come up with things like a stiff, light two-door coupe chassis, rear-wheel-drive with an independent suspension all the way around (and lots of aftermarket parts to tweak it with), and a slick-shifting manual transmission. You’d keep it simple to make it affordable, and most importantly, you’d give it a rev-happy engine, perhaps with a turbo.

Mazda got close to nailing that formula with the first-gen RX-7, but dropped the ball with a live axle rear end. The FC RX-7 cured that deficiency, but got a bunch heavier and more expensive in the process. They’d move back in the right direction with the NA Miata, but despite its basic goodness, it was a hard car to take seriously, and being available only as a convertible didn’t help. Porsche’s 924 and 944 checked all the boxes except for “simple and affordable,” and Toyota and Mitsubishi took a run at it with the original MR2 and the Starion, respectively, but between the MR2’s mid-rear engine layout and Mitsubishi’s trademark general ‘80s high-tech weirdness in the Starion, neither of that Japanese pair really hit the mark, either.

Only one manufacturer managed to artfully combine all those elements into a single platform – in 1989, Nissan introduced the S13 to the world, and a legend was born. Previous generations of the S platform had been successful in their own right, dating all the way back to 1975’s S10, which was known in the US market as the Datsun 200SX. The S110 and S12 followed in 1979 and 1984, respectively, and while they sold well enough both in Japan and abroad, they would barely hint at how popular the next revision would turn out to be.

In the native Japanese market, Nissan was sure enough of success with the new S13 to produce and sell the car in two cosmetically different but mechanically identical models; the hatchback, hidden-headlight 180SX, and the notchback, exposed-headlight Silvia. The two models were sold through separate marketing channels, with the 180SX as the “little brother” to the Fairlady Z and the Silvia retailed alongside the Skyline.

Pop the Hood

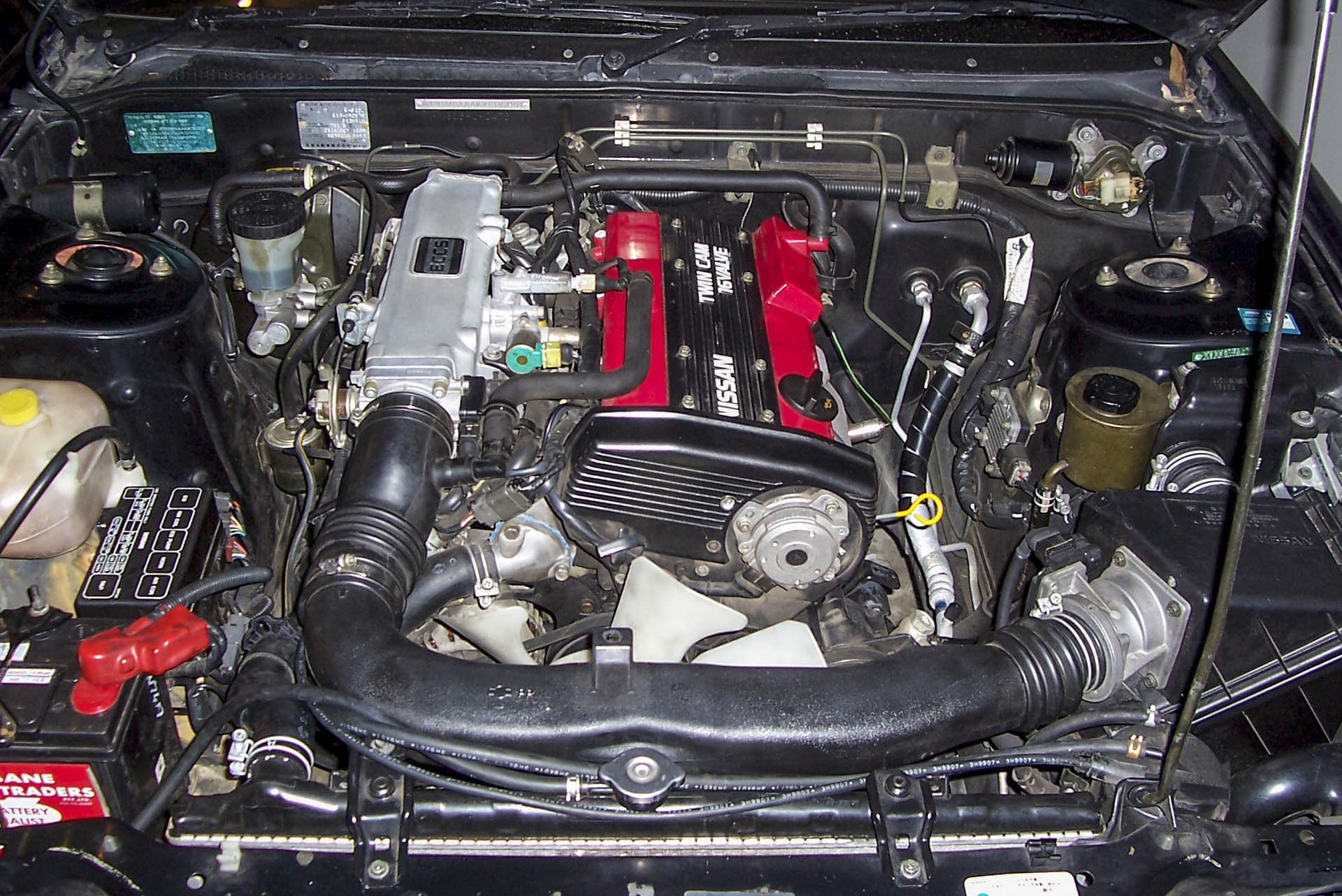

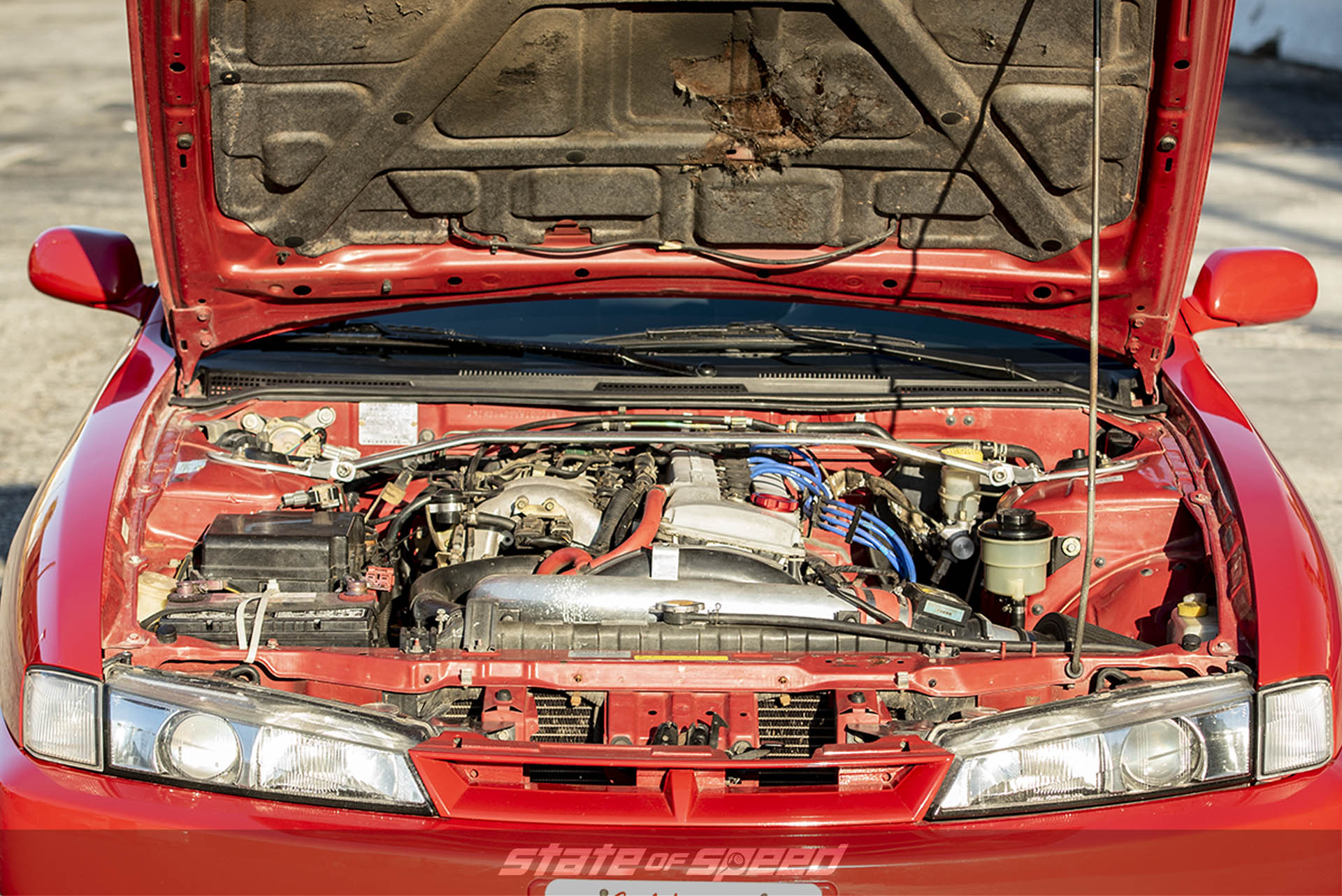

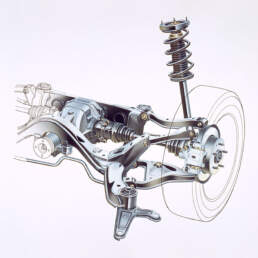

Power for the S13 was initially derived from the iron-block 1.8 liter CA18DE or CA18DET, with the former being naturally aspirated and rated at 131 horsepower, and the latter turbocharged to produce an advertised 166 horsepower. Silvia buyers could select either powerplant, but the 180SX wasn’t produced in a non-turbo version. The free-revving dual overhead cam engine was a good match for the S13’s light weight and balanced chassis, which featured one of Nissan’s first sophisticated multi-link independent rear suspension systems paired with the ubiquitous MacPherson strut setup in front.

At launch for the 1989 model year, Nissan also decided that the S13 would be a good addition to their US car lineup. Only the 180SX would make the trip across the Pacific, though, and to avoid the time and expense required to “Federalize” the CA18, a different engine already destined for Nissan’s American vehicle lineup took its place – the KA24.

This is the point in our story where many of you will hear a sad trombone briefly playing in your head.

While the KA24 did indeed pick up a significant amount of displacement over the CA18 (no points for guessing that it was a 2.4 liter engine), that was about the nicest thing anyone had to say about it at the time. The vast majority of KA engines in US models ended up under the hood of Hardbody trucks and Pathfinder SUVs where its torquey long-stroke design made perfect sense. Like so many engines of the era, the KA24 used a cast-iron block with an aluminum head, and the valvetrain was driven by a timing chain rather than a belt. The engine was significantly “under-square” with an 89mm cylinder bore and 96mm crankshaft stroke, optimized for bottom-end torque capacity rather than high-RPM horsepower potential. 1989-90 USDM 240SX models got the SOHC, 3-valve-per-cylinder KA24E, rated at a less-than-thrilling 140 horsepower, 26 ponies down from the CA18DET in the 1989 180SX.

Coming to America

All US S13 models would be available in both hatchback and notchback body styles, and in the 1992 model year, a convertible based on the notch was introduced, with the drop-top modification performed by American Specialty Cars in California. They all shared the same 180SX-style hidden headlight nose, but as early cars entered the used car market and ended up with front end damage thanks to drivers with more enthusiasm than skill, it became fashionable to replace the hidden headlight front bumper, hood, and fenders with Silvia sheetmetal imported from Japan. While the “Sileighty” trend started in the S13’s home country (as it was usually cheaper in Japan to convert a crashed 180SX to a Silvia front clip than replace the stock parts), in the US its popularity was driven by cosmetic concerns as well as the fact that ditching the US-spec energy absorbing front bumper and the pop-up headlights typically saved 30-plus pounds on the nose of the car.

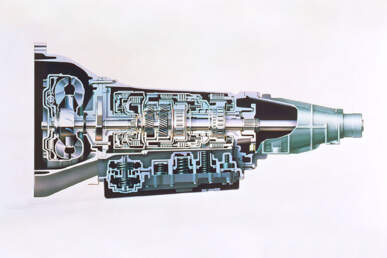

For 1991, the 240SX got a cosmetic facelift that (among other changes) replaced the “pignose” front fascia with one that retained the hidden headlights but had more of an aerodynamic, rounded look. The 240SX also got four more exhaust valves and an extra camshaft with the DOHC KA24DE engine, picking up another 15 horsepower in the process to a total of 155. This engine would remain as the only available powerplant for the duration of the S-chassis’ run in the US market, while in-the-know Nissan fans gazed longingly at the turbocharged 202-horsepower SR20DET that was standard equipment for the 180SX in Japan and other markets, starting in 1991.

For the 1994 model year, Nissan comprehensively reworked the S-chassis and launched the S14 Silvia in the home market, while keeping the previous S13 180SX in production as well through 1998. The hatchback body style was gone for the S14, leaving only the coupe version, and the overall look of the car took on a much more rounded design language. Another minor restyling for the 1997 model year brought an angular and aggressive look to the S14, and spawned the terms “Zenki” and “Kouki” to distinguish the two variations – colloquially “before and after” in Japanese.

Production of the S14 ended in 1998, replaced by the S15 in other markets, but the 1999 model year 240SX was the end of the line in the US. While it was reasonably successful in America, the uninspiring engine, lack of interior room, and relatively poor fuel economy put the 240SX in the position of being too slow to be a standout sports car, and too thirsty and impractical to compete favorably with the many FWD alternatives on the market at the time.

Second Wind

The real success of the Nissan 240SX in the United States happened not at the dealerships but when the cars began to hit the used market. As one of the few Japanese RWD imports (and certainly the most affordable, compared to cars like the MKIV Supra and Lexus IS/Altezza) it was perfectly suited to the rise of grassroots interest in drifting in America. It didn’t hurt that a huge amount of aftermarket support was also available from well-known Japanese tuners (and sketchy eBay knockoffs) for owners looking to upgrade the suspension and driveline. The primary hurdle, however, was that “truck engine” under the hood.

The KA engine family never inspired much interest in performance modification outside the United States, meaning that homegrown solutions to increasing output tended to be the norm for those who didn’t want to pull the trigger on a full engine swap. KA-T turbocharged conversions of varying levels of sophistication and build quality were the go-to option, and Turbonetics actually offered a complete T3/T4 hybrid kit pushing 8 PSI for 1995-1998 models that bumped rated horsepower to 240 at the crank. Though the KA’s architecture was definitely overbuilt for how lightly-stressed it was in factory tune, that strength was a boon for anyone strapping on a turbo. It didn’t hurt that lightly-used takeout KA engines from both swapped 240s and a whole generation of pickups and Frontiers were cheaply available in salvage yards, either.

The primary hurdle, however, was that “truck engine” under the hood.

During the heyday of import and sport compact racing in the US, circa the mid-2000s, far and away the most popular engine swap for stateside 240SXs was the SR20DET. As mentioned before, this powerplant was standard equipment in 1991 and later 180SX models. Originally developed with a transverse FWD layout for the JDM Nissan Bluebird, the SR came in many forms over its long history in factory S13/14/15 applications. The different specifications are broadly grouped into a few categories based on the factory paint applied to the valve cover or its shape, making for a quick visual reference.

| “Red Top” 1991-1993 180SX Silvia |

“Black Top” 1994-1998 S13 180SX |

“Notch Top” 1994-1998 S14 Silvia |

“Notch Top” 1999-2002 S15 Silvia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turbo | Garrett T25G | Garrett T25G | Garrett T28G | Garrett T28G |

| Compression | 8:5:1 | 8:5:1 | 8:5:1 | 8:5:1 |

| Boost | 7psi | 7psi | 7psi | 7psi |

| Horsepower | 205hp | 205hp | 217hp | 247hp |

| Additional Features | – | – |

|

|

This only covers the S13/14/15 factory applications for the SR20DET; in transverse front wheel and all wheel drive configuration it found a home in many other platforms, including a WRC Group A homologation version of the Japanese market Pulsar. With so many variations, the SR spawned a good deal of interest in swaps for US S-series cars, and even supported shops and tuners who specialized in that market for a few glorious years. Despite the fact that the SR had never been used in any Nissan sold in the US market, shipping containers full of them made their way to the pier at Long Beach and into the hands of American enthusiasts, a phenomenon made economically viable by the odd Japanese vehicle tax and registration laws that encouraged owners of cars more than a few years old to scrap them rather than keep them on the road.

Reaching Classic Status

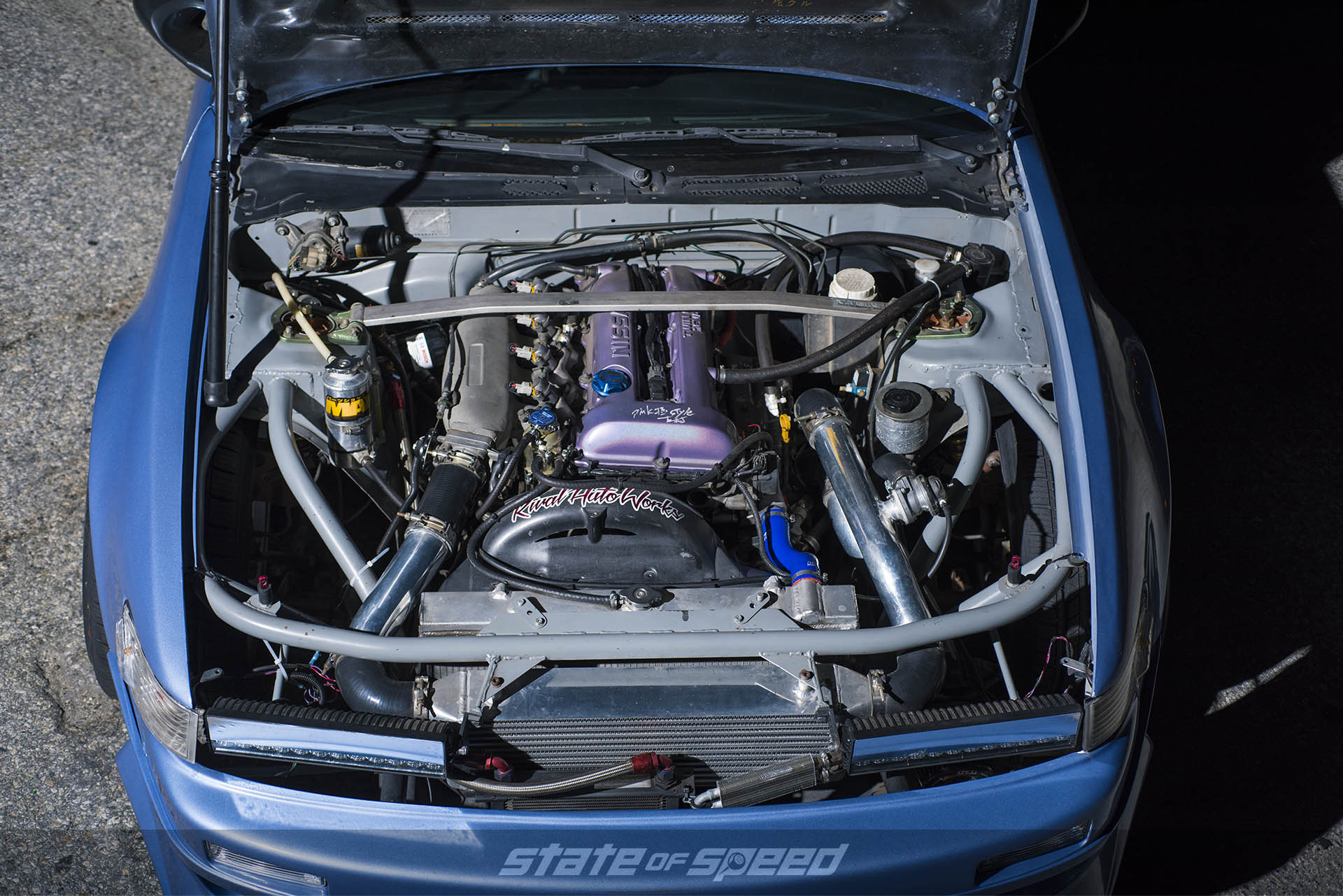

Today, the Nissan 240SX is reaching the same status as the Datsun 510 achieved in the 90’s – clean, unmolested examples have reached the bottom of their depreciation curve and are heading upward in price as they become harder to find and more sought-after as competitive drift cars and daily drivers. Perhaps the single greatest influence on the current popularity of the S13/14 in the US is the fact that so many different powerplants, including Gen III/IV GM small-block V8 engines, are an easy fit into the 240SX’s generously-sized engine bay, making a naturally-aspirated 350+ horsepower swap fairly straightforward. Companies like Holley’s Hooker brand even make specific swap components (cast manifolds and tubular headers, engine mounts, and more) for LS swaps into S-chassis cars.

A look at the grid for any drift event will show the “sportsman” categories heavily favor S13 and S14 builds; while the pro categories tend to have newer cars better represented due to bigger budgets for parts development and chassis testing, the Silvia is still the standard against which all other modern drift platforms are compared. All the kinks have been worked out, and there’s no need to reinvent the wheel when building a competition car from an S13 or S14 – practically any component you can imagine, from coilovers, handbrakes, cages, and even all the way to full upgraded suspension setups are available off-the-shelf, and often from multiple manufacturers.

The 240SX might not have been the perfect car straight off off US Nissan dealers’ showroom floors, but it was close enough to make it a highly-desirable future classic in stock or full-drift form, or anything in between.

updated July 22, 2021

Isn’t this a bit dated?

I mean 240s are so “classic” now that every one you find is a drift missile asking too much.

I think we’re reaching the end of the 240 dominance as used 350z and BRZ are hitting the market super cheap to use for drifting.

Plus for most Street Legal leagues both the FRs/BRZ and the 350z can run it without caging thanks to new safety designs.